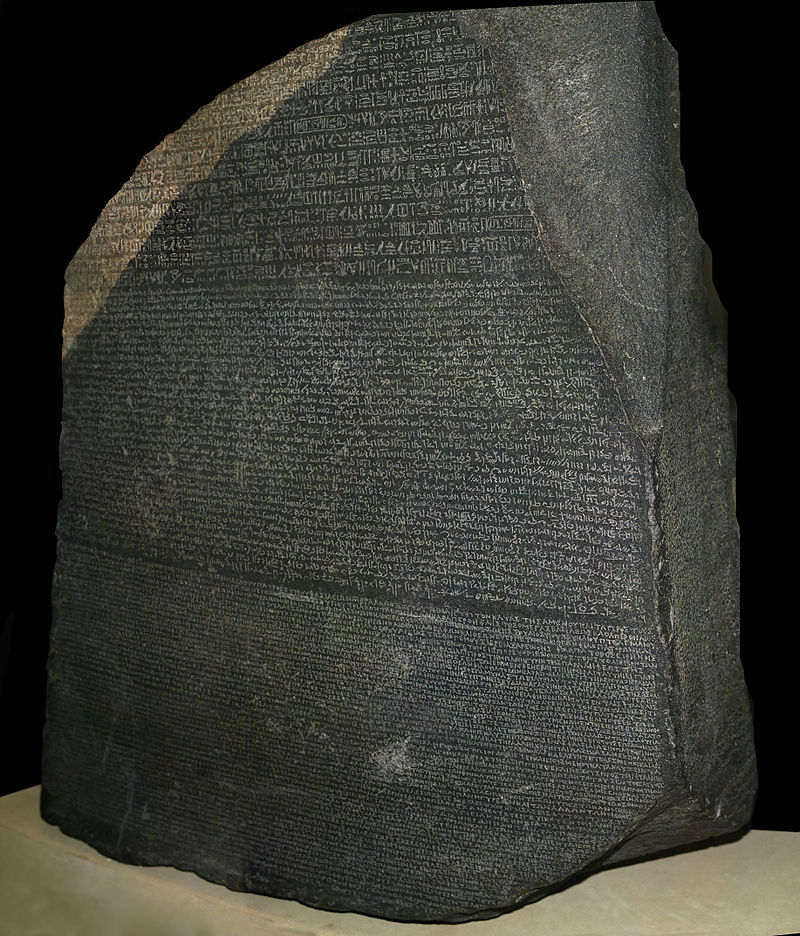

The Rosetta Stone at the British Museum – This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. Attribution: © Hans Hillewaert

The Rosetta Stone is a granite stele found in 1799, inscribed in hieroglyphic script, Demotic and ancient Greek. It proved to be the key to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs, opening a window to Egypt’s civilization, history and heritage.

Rosetta Stone is also a brand and a trademark, for a company specializing in language translation software.

That trademark reference led to a UDRP for the domain name, RosettaStone.app. The Respondent is a British expatriate, who asserted that the British Museum’s hosting of the stele motivated his registration of the domain.

Rosetta Stone Ltd. of Harrisonburg, Virginia, United States of America provided proof of several trademark registrations, going back to 2003. Meanwhile, RosettaStone.app is currently undeveloped.

The Respondent was represented by ESQwire, a law firm that is a sponsor of DomainGang. We acquired this decision’s document directly from the WIPO.

The Respondent noted, through their council, that the domain’s intended use does not infringe on the Complainant’s marks, as it’s a generic reference to the actual Rosetta Stone stele, along with a description of its intended use:

[…] the Complainant does not have exclusive rights to the name “Rosetta Stone” given to the stone discovered in Rosetta, Egypt, that was used to decipher the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, and which is a globally recognized historically relevant object currently on display at the British Museum. According to the Respondent, the Complainant’s own use of the ROSETTA STONE brand is not arbitrary, but is suggestive of the Rosetta Stone artefact. Though the Complainant holds a valid trademark for ROSETTA STONE it does not have a monopoly on referring to the historic object Rosetta Stone or to use the term “Rosetta Stone” in connection with a product designed to unlock, translate or decipher complicated matters and mysteries such as the Respondent’s product, which will reveal the locations of preferred and permitted dive sites and will connect scuba divers to boats to safely explore these areas.

The three member panel at the WIPO delivered a finding favoring the Complainant; a key factor being the lack of demonstrating any active development for the domain name.

One panelist, The Hon Neil Brown Q.C., dissented, voting for the Respondent:

It is disappointing that this is another decision that prevents people from registering domain names that are simply part of the common language that belongs to everyone. It is perhaps more unfortunate that not only does the decision deny the use as a domain name of words that are in common use by the community and as part of its normal discourse, but it also negates a domain name that adopts the name of a well-known historical object, the Rosetta Stone, a use that should also be available to all people and a name that the Complainant itself has taken for its own trademark.

The Respondent has registered a domain name that is not in breach of the Complainant’s trademark. The Respondent has then declared a proposed use for the domain name that is also not in breach of that trademark, and well beyond the scope of the trademark. It is also a use that fits easily within the generic meaning of the domain name.

Full details on the decision for RosettaStone.app follows:

Copyright © 2025 DomainGang.com · All Rights Reserved.WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center

ADMINISTRATIVE PANEL DECISION

Rosetta Stone Ltd. v. Digital Privacy Corporation / Stuart Thomas

Case No. D2018-23221. The Parties

The Complainant is Rosetta Stone Ltd. of Harrisonburg, Virginia, United States of America (“United States”), represented by CSC Digital Brand Services Group AB, Sweden.

The Respondent is Digital Privacy Corporation of California, United States / Stuart Thomas of Los Angeles, California, United States, represented by ESQwire.com P.C., United States.

2. The Domain Name and Registrar

The disputed domain name <rosettastone.app> is registered with 101domain, Inc. (the “Registrar”).

3. Procedural History

The Complaint was filed with the WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center (the “Center”) on October 12, 2018. On October 12, 2018, the Center transmitted by email to the Registrar a request for registrar verification in connection with the disputed domain name. On October 19, 2018, the Registrar transmitted by email to the Center its verification response disclosing registrant and contact information for the disputed domain name, which differed from the named Respondent and contact information in the Complaint. The Center sent an email communication to the Complainant on October 22, 2018, providing the registrant and contact information disclosed by the Registrar, and inviting the Complainant to submit an amendment to the Complaint. The Complainant filed an amended Complaint on October 24, 2018.

The Center verified that the Complaint together with the amended Complaint satisfied the formal requirements of the Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (the “Policy” or “UDRP”), the Rules for Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (the “Rules”), and the WIPO Supplemental Rules for Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (the “Supplemental Rules”).

In accordance with the Rules, paragraphs 2 and 4, the Center formally notified the Respondent of the Complaint, and the proceedings commenced on October 25, 2018. In accordance with the Rules, paragraph 5, the due date for Response was November 14, 2018. On November 14, 2018, the Respondent requested an automatic four-day extension to submit a Response under paragraph 5(b) of the Rules. On November 16, 2018, the Respondent was granted an additional extension of time to file a Response until November 21, 2018. The Response was filed with the Center on November 21, 2018. On November 27, 2018, the Center received a supplemental filing from the Complainant. On December 7, 2018, the Center received a supplemental filing form the Respondent. The Complainant submitted a reply to the Respondent’s supplemental filing on December 12, 2018. The Respondent submitted a reply to the Complainant’s second supplemental filing on December 14, 2018.

The Center appointed Assen Alexiev, Luca Barbero, and The Hon Neil Brown Q.C. as panelists in this matter on January 7, 2019. The Panel finds that it was properly constituted. Each member of the Panel has submitted the Statement of Acceptance and Declaration of Impartiality and Independence, as required by the Center to ensure compliance with the Rules, paragraph 7.

Exercising its powers under paragraphs 10 and 12 of the Rules, the Panel has decided to accept the supplemental filings of the Parties and to take them into account, as they deal with issues that the Parties were not in a position to take into account and discuss in the Complaint and in the Response.

4. Factual Background

The Complainant was established in 1992 as Fairfield Language Technologies. In 2006, the company was renamed to Rosetta Stone Ltd. The Complainant offers interactive language-learning products for the study of 30 languages, including its Rosetta Stone mobile application available in Google Play and in the Apple App Store. The Complainant has offices in various cities in the United States, Tokyo, Seoul, London, Dubai, and Sao Paulo, and is a publicly traded company on the New York Stock Exchange.

The Complainant is the owner of the following trademark registrations for “Rosetta Stone” (the ROSETTA STONE trademark):

– the trademark ROSETTA STONE with registration No. 2761492, registered on September 9, 2003 in the United States for goods in International Class 9;

– the trademark ROSETTA STONE with registration No. 3569720, registered on February 3, 2009 in the United States for services in International Class 38;

– the trademark ROSETTA STONE with registration No. 3749526, registered on February 16, 2010 in the United States for services in International Class 42;

– the trademark ROSETTA STONE with registration No. 4019088, registered on August 30, 2011 in the United States for services in International Class 41;

– the European Union trademark ROSETTA STONE with registration No. 004779864, registered on January 18, 2007 for goods and services in International Classes 9, 16, and 41;

– the European Union trademark ROSETTA STONE with registration No. 010327062, registered on February 1, 2012 for services in International Classes 38, 41, and 42; and

– the trademark ROSETTA STONE with registration No. TMA627854, registered on December 8, 2004 in Canada for goods and services in International Classes 9, 38, 41, and 42.The Complainant’s official website is located at the domain name <rosettastone.com>.

The disputed domain name was registered on May 8, 2018. It is currently inactive.

5. Parties’ Contentions

A. Complainant

The Complainant submits that its ROSETTA STONE trademark is well recognized by consumers, industry peers and the broader global community as a result of the Complainant’s significant investments over the years to advertise, promote, and protect the ROSETTA STONE trademark through various forms of media, including the Internet. The Complainant’s primary website at “www.rosettastone.com” has received 2.56 million visitors in the past six months according to Similarweb.com, and Alexa.com ranks it as the 5,802nd most popular site in the United States and 17,968th in the world. In Google Play, the Complainant’s Rosetta Stone mobile application has been installed by more than five million users, while the Apple Store ranks the same mobile application at No. 25 in the education category with a rating of 4.7 out of 5. The Complainant received the 2017 Tabby Awards for the best iOS phone application and the best Android phone application in the education category, and together with Siemens Professional Education, the Complainant won the eLearning Award 2018 for the most innovative workplace learning program.

According to the Complainant, the disputed domain name is identical to the ROSETTA STONE trademark in which the Complainant has rights, as it incorporates the trademark in its entirety.

The Complainant claims that the Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in respect of the disputed domain name. The granting of trademark registrations to Complainant for the ROSETTA STONE trademark is prima facie evidence of the validity of “rosetta stone” as a trademark, of the Complainant’s ownership of this trademark, and of the Complainant’s exclusive right to use it. The Complainant points out that the Respondent is not commonly known by the disputed domain name, and the WhoIs information for the disputed domain name identifies its registrant as Stuart Thomas, which name does not resemble the disputed domain name. The Complainant adds that it has not licensed, authorized, or permitted the Respondent to register domain names incorporating the Complainant’s ROSETTA STONE trademark, and points out that the disputed domain name redirects Internet users to a blank page without content. According to the Complainant, the Respondent has failed to make use of this disputed domain name and has not demonstrated any legitimate use of it. The Complainant also refers to the fact that the Respondent registered the disputed domain name on May 8, 2018, which is many years after the Complainant applied for registration and commenced the use of its ROSETTA STONE trademark in 1992 and after it registered the <rosettastone.com> domain name in 1999.

With its supplemental submissions, the Complainant points out that the Respondent has not offered any verifiable evidence for the use of the disputed domain name or for any preparations to use the disputed domain name in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services. The declaration submitted by the Respondent is self-serving, not inherently credible and not supported by relevant pre-Complaint evidence. The Complainant disputes that the evidence submitted by the Respondent “is highly suggestive of the types of existing services offered and intended to be offered”, because it is not supported by evidence of a relationship between the Respondent’s existing products or services and the disputed domain name. The Respondent’s current products make no reference to the disputed domain name and do not reflect any use or intention to use it.

The Complainant states that the Respondent does not deny that the Complainant’s ROSETTA STONE trademark is well known, and that the Respondent was aware of the Complainant and its rights when registering the disputed domain name. The existence of Complainant’s Rosetta Stone app on every major mobile application platform today is further evidence in this regard. The Complainant states that when a distinctive well-known mark is involved, past panels have tended to view with a degree of skepticism a respondent’s defense that the domain name was merely registered for legitimate speculation based on a dictionary meaning as opposed to targeting a specific brand owner. The Complainant points out that the ROSETTA STONE trademark possesses substantial inherent and acquired distinctiveness, and the awareness of it is considered to be significant. According to the provisions of Article 6bis of the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property (“Paris Convention”), extended by Article 16.2 and Article 16.3 of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (“TRIPS Agreement”), the statute of a well-known trademark provides the owner of such a trademark with the right to prevent any use of the well-known trademark or a confusingly similar denomination in connection with any products or services. Thus, the protection of the ROSETTA STONE trademark goes far beyond language learning programs. According to the Complainant, the Respondent’s denial of the global popularity of the Complainant’s Rosetta Stone software is unreasonable. The Complainant refers to a CNN article on the Complainant’s Rosetta Stone software, which describes it as the gold standard of computer-based language learning.

The Complainant contends that the disputed domain name was registered and is being used in bad faith. In support of this contention, the Complainant again points out that it and its ROSETTA STONE trademark are known internationally, that the Complainant is one of the world’s leading providers of digital language learning programs used by millions of users worldwide, and that searches in Internet search engines for “rosettastone” return multiple links referencing the Complainant and its business. The Complainant also submits that it has marketed and sold its goods and services using the ROSETTA STONE trademark since 1993, which is well before the Respondent’s registration of the disputed domain name on May 8, 2018.

According to the Complainant, at the time of registration of the disputed domain name the Respondent knew or should have known of the existence of the Complainant’s trademarks. With its supplemental submissions, the Complainant further points out that with its Response the Respondent has acknowledged that it was aware of the Complainant’s rights in the ROSETTA STONE trademark when registering the disputed domain name, and has recognized that the ROSETTA STONE trademark is well known.

The Complainant states that the disputed domain name currently resolves to an inactive site and is not being used, and that the passive holding of a domain name can constitute a factor in finding bad faith registration and use pursuant to the Policy. The Complainant maintains that it is more likely than not that the Respondent targeted the Complainant’s ROSETTA STONE trademark. According to the Complainant, the disputed domain name is intended to cause confusion among Internet users as to its source, and must be considered as having been registered and used in bad faith, since there is no plausible good-faith reason or logic for the Respondent to have registered the disputed domain name, and the only feasible explanation for the registration of the disputed domain name is that the Respondent intends to cause confusion, mistake and deception by means of the disputed domain name, so that any use of the disputed domain name for an actual website could only be in bad faith.

The Complainant also refers to the fact that at the time of filing of the Complaint the Respondent had employed a privacy service and that it did not respond to the Complainant’s cease-and-desist letters sent before the commencement of this administrative proceeding.

B. Respondent

The Respondent maintains that there is no basis for transferring the disputed domain name to the Complainant. The Respondent does not dispute that the Complainant has a well-known and popular language learning program, but points out that the Complainant does not have exclusive rights to the name “Rosetta Stone” given to the stone discovered in Rosetta, Egypt, that was used to decipher the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, and which is a globally recognized historically relevant object currently on display at the British Museum. According to the Respondent, the Complainant’s own use of the ROSETTA STONE brand is not arbitrary, but is suggestive of the Rosetta Stone artefact. Though the Complainant holds a valid trademark for ROSETTA STONE it does not have a monopoly on referring to the historic object Rosetta Stone or to use the term “Rosetta Stone” in connection with a product designed to unlock, translate or decipher complicated matters and mysteries such as the Respondent’s product, which will reveal the locations of preferred and permitted dive sites and will connect scuba divers to boats to safely explore these areas. According to the Respondent, the Complainant was neither the first nor the last company to use the term “Rosetta” in connection with translation systems and software, and many third-party products have used this term in connection with its suggestive meaning, associated with unlocking a code or providing the key to discovering something hidden or inaccessible.

The Respondent states that it is a British ex-patriot currently living in Los Angeles who was raised in the United Kingdom where the Rosetta Stone is on display. It is a software developer and scuba diver since the early 1990s. It is also a licensed PADI open water scuba instructor since 1994, and has taught scuba diving for many years in various countries and locations, including in the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. Many of the Respondent’s clients were European and the most popular wreck and exploratory dive locations were in and around the Egyptian Mediterranean Sea.

The Respondent does not question the validity and recognition of the Complainant’s product and of the ROSETTA STONE trademark and accepts that the disputed domain name is identical to Complainant’s trademark, but states that the Complainant does not have exclusive rights to the name “Rosetta Stone” and that other entities have also referred to the actual Rosetta Stone for inspiration and associative properties to their products and services.

The Respondent further alleges that it has rights and a legitimate interest in the disputed domain name because it identifies the well-known Rosetta Stone. The Respondent also refers to a scuba diving and tour boat called “Rosetta” and mentions a dive site in the Philippines called “Rosetta’s Stone ”. The Respondent’s company Beyond Connect, LLC develops diving related software, and offers a mobile phone application for the scuba diving community called “BLU”. The Respondent states that it sought to register “.app” domain names, but the domain name <blu.app> was already taken, so it began to explore other brandable options. It was attracted to the disputed domain name because of the actual Rosetta Stone, and registered it when it first became available for registration for a purpose unrelated to the Complainant’s language translation and learning services. According to the Respondent, long prior to the notice of this dispute, it began the development of an expanded application project to be called “Rosetta Stone”, to help scuba divers discover diving locations and schedule boats for such dives, but this project and the related capital raise and rebranding are not yet completed. For the purposes of this project, the Respondent registered the disputed domain name to associate its new product with the well-known meaning of the Rosetta Stone and to create a suggestive connection between the Rosetta Stone’s properties and the Respondent’s product.

The Respondent contends that it is not a cybersquatter, and it did not register, has not used, and will not be using the disputed domain name in bad faith with the intent to sell it to the Complainant, to disrupt the Complainant’s business, to prevent it from registering a domain name reflecting its trademark, or to confuse users. The Respondent registered an available, highly valuable common word domain name, and there is no evidence that the Respondent registered the disputed domain name to target the Complainant or its ROSETTA STONE trademark. The Respondent also notes that “.app” is a new generic Top-Level Domain (“gTLD”) with a Sunrise registration period and is subject to the protections of the Trademark Clearing House (TMCH). The Complainant’s trademark was listed in the TMCH, and if the Complainant really believed that the disputed domain name was inextricably linked and central to its product and trademark it could have registered the disputed domain name during the Sunrise registration period and before the general public.

6. Discussion and Findings

Pursuant to the Policy, paragraph 4(a), the Complainant must prove each of the following to justify the transfer of the disputed domain name:

(i) the disputed domain name is identical or confusingly similar to a trademark or service mark in which the Complainant has rights;

(ii) the Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in respect of the disputed domain name; and

(iii) the Respondent has registered and is using the disputed domain name in bad faith.

A. Identical or Confusingly Similar

The Complainant has provided evidence for several registrations of the ROSETTA STONE trademark in the United States, the European Union, and Canada, covering goods and services in International Classes 9, 16, 38, 41, and 42. The Respondent has not disputed the existence and validity of these trademark registrations, and they satisfy the Panel that the term “rosetta stone” may be registered as a trademark and that the Complainant has an exclusive right in the respective jurisdictions to use the ROSETTA STONE trademark for the goods and services that fall within the scope of these trademark registrations, including software products.

The Panel notes that as discussed in section 1.11 of the WIPO Overview of WIPO Panel Views on Selected UDRP Questions, Third Edition (“WIPO Overview 3.0”), the applicable TLD in a domain name is viewed as a standard registration requirement and as such is disregarded under the first element confusing similarity test. The practice of disregarding the TLD in determining identity or confusing similarity is applied irrespective of the particular TLD, including new gTLDs, and the ordinary meaning ascribed to a particular TLD would not necessarily impact assessment of the first element. The meaning of such TLD may however be relevant to panel assessment of the second and third elements. The Panel sees no reason not to follow the same approach here, so it will disregard the “.app” gTLD section of the disputed domain name for the purposes of assessing whether the disputed domain name is identical or confusingly similar to the ROSETTA STONE trademark of the Complainant.

The relevant part of the disputed domain name is therefore “rosettastone”. It consists of the elements “rosetta” and “stone”. The combination of these elements is identical to the ROSETTA STONE trademark. In view of this, the Panel finds that the disputed domain name is identical to the ROSETTA STONE trademark in which the Complainant has rights. It is also worth mentioning that the Respondent does not dispute this conclusion.

B. Rights or Legitimate Interests

While the overall burden of proof in UDRP proceedings is on the complainant, panels have recognized that proving a respondent lacks rights or legitimate interests in a domain name may result in the often-impossible task of “proving a negative”, requiring information that is often primarily within the knowledge or control of the respondent. As such, where a complainant makes out a prima facie case that the respondent lacks rights or legitimate interests, the burden of production on this element shifts to the respondent to come forward with relevant evidence demonstrating rights or legitimate interests in the domain name. If the respondent fails to come forward with such relevant evidence, the complainant is deemed to have satisfied the second element. See section 2.1 of the WIPO Overview 3.0.

The Complainant contends that the Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in the disputed domain name, stating that the Respondent has not been authorized by the Complainant to use the ROSETTA STONE trademark and that the Respondent is not commonly known by the disputed domain name, and pointing out that the disputed domain name redirects Internet users to a blank page. With its supplemental submission, the Complainant maintains that the Respondent has not offered any verifiable evidence for the use of the disputed domain name or for any preparations to use the disputed domain name in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services, and that there is no relationship between the Respondent’s existing products or services and the disputed domain name. The Complainant further points to the fact that the Respondent does not deny that the Complainant’s ROSETTA STONE trademark is well known, and that the Respondent was aware of the Complainant and its rights when registering the disputed domain name.

The Respondent alleges that is has rights and legitimate interests in the disputed domain name. It points out that the Complainant does not have exclusive rights to the name of the Rosetta Stone artefact, and the Complainant’s ROSETTA STONE trademark does not give it a monopoly to the use of the term “Rosetta Stone” in connection with a product designed to unlock, translate or decipher complicated matters or mysteries, such as the new product to be called “Rosetta Stone” that the Respondent’s company Beyond Connect, LLC started to develop long prior to the notice of this dispute to help scuba divers discover diving locations and schedule boats for such dives. The Respondent maintains that it registered the disputed domain name to associate its new product with the well-known meaning of the historic Rosetta Stone and to create a suggestive connection between its properties and the Respondent’s product.

Having examined the arguments of the Parties and the evidence submitted by them, the majority of the Panel has reached the conclusions that follow.

The arguments and evidence submitted by the Respondent do not satisfy the majority of the Panel that the Respondent has registered the disputed domain name because of the historic Rosetta Stone or for a purpose unrelated to the Complainant. The Respondent claims that “long prior to the notice of this dispute” it had commenced the development of a mobile phone application to be called Rosetta Stone, but there is not a single piece of evidence in the case file to support this statement. It should be expected that when an experienced company such as the Respondent’s starts the development of a significant new product, this would naturally lead to the creation of a number of documents about the project, such as marketing concepts (including in relation to the possible names for the new product), business plans, internal correspondence between team members developing the project, documents related to the financing of the project (such as documents for a capital increase, which the Respondent notably mentions that it needs time to carry out for the purposes of its new project), etc. The Respondent has provided evidence about its existing BLU application, but this evidence does not show any connection between this application and the Rosetta Stone artefact, and the Panel does not understand how the use of the disputed domain name for the offering of a commercial software product can be regarded as use in relation to a historic artefact. In view of this, the majority of the Panel is not convinced that the Respondent has indeed started the development of a new mobile phone application to be called Rosetta Stone, or that prior to the notice of the dispute it had commenced preparations for use of the disputed domain name in relation to the Rosetta Stone artefact. This makes the majority of the Panel question what the real motives of the Respondent for registering the disputed domain name were, since the explanations given by it are not convincing.

The disputed domain name is identical to the Complainant’s ROSETTA STONE trademark and is registered in the “.app” TLD, where the Respondent confirms to have been seeking to register domain names for its “apps”, or mobile phone applications. The majority of the Panel understands this interest of the Respondent in the “.app” TLD, because it is descriptive of “apps”. At the same time, it is undisputed that the Complainant has a well‑known language learning product, offered also as an “app” in Google Play and Apple App Store, and the Respondent does not dispute its knowledge of the Complainant or that the Complainant’s product and trademark are well known. The Respondent has also provided evidence that it has received a notice of the Complainant’s ROSETTA STONE trademark registration from the TMCH. After this notice, it nevertheless proceeded with the registration of the disputed domain name. As discussed in section 2.14.1 of the WIPO Overview 3.0, when the TLD is descriptive of or relates to goods or services or other term associated with the complainant, the respondent’s selection of such TLD would tend to support a finding that the respondent obtained the domain name to take advantage of the complainant’s trademark and as such that the respondent lacks rights or legitimate interests in the domain name.

Even if the Respondent did not target the Complainant’s trademark (for such targeting there indeed is no direct evidence in the case file), the circumstances of this case support a conclusion that the Respondent is likely to have proceeded with the registration of the disputed domain name in the “.app” TLD with knowledge that the Complainant has a well-known and popular trademark (which is registered for a number of goods and services, including software) and language learning program (also in the form of a mobile phone application) called Rosetta Stone. In such circumstances, and especially if the Respondent’s allegation that it intended to use the disputed domain name for its own mobile phone application also to be called Rosetta Stone is accepted, the majority of the Panel would expect a professional software developer such as the Respondent to ask itself (and quite possibly its professional advisors as well) whether the use of the disputed domain name and the offering of its mobile phone application under the name Rosetta Stone might create a risk of confusion of consumers including an association of the Respondent’s product with the Complainant, and whether such use would not represent an act of unfair competition. It appears to the majority of the Panel as more likely than not that the Respondent, being more or less aware of the above risks, nevertheless accepted them and proceeded with the registration of the disputed domain name. The Panel does not regard such conduct as being carried out in good faith.

On the basis of all the above, the majority of the Panel has reached the conclusion that the Respondent has not established that it has rights or legitimate interests in the disputed domain name. Therefore, the majority of the Panel finds that the Respondent does not have rights or legitimate interests in the disputed domain name.

C. Registered and Used in Bad Faith

Paragraph 4(b) of the Policy lists four illustrative alternative circumstances that shall be evidence of the registration and use of a domain name in bad faith by a respondent, namely:

“(i) circumstances indicating that you have registered or you have acquired the domain name primarily for the purpose of selling, renting, or otherwise transferring the domain name registration to the complainant who is the owner of the trademark or service mark or to a competitor of that complainant, for valuable consideration in excess of your documented out-of-pocket costs directly related to the domain name; or

(ii) you have registered the domain name in order to prevent the owner of the trademark or service mark from reflecting the mark in a corresponding domain name, provided that you have engaged in a pattern of such conduct; or

(iii) you have registered the domain name primarily for the purpose of disrupting the business of a competitor; or

(iv) by using the domain name, you have intentionally attempted to attract, for commercial gain, Internet users to your website or other online location, by creating a likelihood of confusion with the complainant’s mark as to the source, sponsorship, affiliation, or endorsement of your website or location or of a product or service on your website or location.”

The provisions of paragraph 4(b) of the Policy are without limitation, and bad faith registration and use may be found on grounds otherwise satisfactory to the Panel. As discussed in section 3.2.1 of the WIPO Overview 3.0, some of the particular circumstances that panels may take into account in assessing whether the respondent’s registration of a domain name is in bad faith include the chosen TLD, particularly where corresponding to the complainant’s area of business activity, and the absence of rights or legitimate interests coupled with no credible explanation for the respondent’s choice of the domain name.

The Respondent confirms having knowledge of the Complainant and of its Rosetta Stone product (including in the form of a mobile phone application) and trademark. The ROSETTA STONE trademark registration was notified to the Respondent by the TMCH. This notice (in relevant parts) contained the following warnings to the Respondent: “You may or may not be entitled to register the domain name depending on your intended use and whether it is the same or significantly overlaps with the trademarks listed below. Your rights to register this domain name may or may not be protected as noncommercial use or “fair use” by the laws of your country. Please read the trademark information below carefully, including the trademarks, jurisdictions, and goods and services for which the trademarks are registered. […] If you have questions, you may want to consult an attorney or legal expert on trademarks and intellectual property for guidance. If you continue with this registration, you represent that, you have received and you understand this notice and to the best of your knowledge, your registration and use of the requested domain name will not infringe on the trademark rights listed below.”

In this proceeding both Parties are located in the United States and the ROSETTA STONE trademark is registered in this jurisdiction for a number of goods and services, including software products. The disputed domain name is identical to the ROSETTA STONE trademark and is registered in the “.app” TLD, which is related to mobile phone applications, such as the one developed by the Complainant and the one that the Respondent alleges to have started developing.

However, as discussed in section 6.B above, the Respondent has not provided any evidence that prior to the notice of the dispute it had started the development of a new mobile phone application to be called Rosetta Stone or that it had started preparations for the use of the disputed domain name in relation to the historic Rosetta Stone. This makes the majority of the Panel question what the real motives of the Respondent for registering the disputed domain name were, since the explanations given by it are not convincing. It cannot be excluded that the Respondent might have decided not to disclose its real motives because such disclosure might be damaging to its position in the present proceeding.

In view of the above, and if the Respondent’s explanation that it plans to use the disputed domain name for the offering of a commercial software product is accepted, the use of the disputed domain name and the offering of a mobile phone application under the name Rosetta Stone might create a risk of confusion for consumers, including an association of the Respondent’s product with the Complainant, and might also represent an act of unfair competition. It appears to the majority of the Panel as more likely than not that the Respondent, being more or less aware of the above risks and of the chances that the disputed domain name might thus improperly benefit from the goodwill associated with the Complainant and its trademark, nevertheless accepted this and proceeded with the registration of the disputed domain name. The majority of the Panel is of the opinion that this conduct of the Respondent supports a finding that it has registered the disputed domain name in bad faith.

The disputed domain name does not resolve to an active website. However, as discussed in section 3.3 of the WIPO Overview 3.0, the non-use of a domain name would not prevent a finding of bad faith under the doctrine of passive holding. Factors that have been considered relevant in applying the passive holding doctrine include the degree of distinctiveness or reputation of the complainant’s mark, the failure of the respondent to provide evidence of actual or contemplated good faith use of the disputed domain name, and the implausibility of any good faith use to which the domain name may be put.

Taking into account the circumstances of this case, the majority of the Panel accepts that many of these factors are present in this dispute. There is no dispute between the Parties that the ROSETTA STONE trademark is well known, and the Respondent has not presented evidence of any actual or contemplated good faith use of the disputed domain name. In view of the scope of protection of the ROSETTA STONE trademark, which includes software products, and the fact that the disputed domain name is registered in the “.app” TLD, which refers to apps, the majority of the Panel accepts that there is a significant risk that the use of the disputed domain name by the Respondent (especially for the planned purpose that it has described) might unduly benefit from the popularity of the Complainant’s ROSETTA STONE trademark, which would not be legitimate.

In view of all the above, the majority of the Panel finds that the Respondent has registered and used the disputed domain name in bad faith.

7. Decision

For the foregoing reasons, in accordance with paragraphs 4(i) of the Policy and 15 of the Rules, the majority of the Panel orders that the disputed domain name <rosettastone.app> be transferred to the Complainant.

Assen Alexiev

Presiding PanelistLuca Barbero

PanelistThe Hon Neil Brown Q.C.

Panelist (Dissenting)

Date: February 27, 2019Dissent by the Honourable Neil Anthony Brown Q.C.

GeneralIt is disappointing that this is another decision that prevents people from registering domain names that are simply part of the common language that belongs to everyone. It is perhaps more unfortunate that not only does the decision deny the use as a domain name of words that are in common use by the community and as part of its normal discourse, but it also negates a domain name that adopts the name of a well-known historical object, the Rosetta Stone, a use that should also be available to all people and a name that the Complainant itself has taken for its own trademark.

The Respondent has registered a domain name that is not in breach of the Complainant’s trademark. The Respondent has then declared a proposed use for the domain name that is also not in breach of that trademark, and well beyond the scope of the trademark. It is also a use that fits easily within the generic meaning of the domain name.

Despite this, a majority of the Panel has decided to deprive the Respondent of its domain name, but not on the ground that any harm is being done to anyone or that there is any breach of the law, and not that there has been any passing off, confusing conduct or targeting by the Respondent, as there clearly has been none, and the majority has expressly decided that there is “no direct evidence”of targeting. “No direct evidence of targeting” means that there is no evidence of targeting. In any event, nor was there even any indirect evidence of targeting. There was therefore no evidence at all that showed, or from which it could be inferred, that the Respondent had registered the domain name with the Complainant or its trademark in mind.

Rather, on the evidentiary findings, it appears that the Respondent is to lose its domain name in a summary procedure simply because the panel “questions” the motives of the Respondent, that its conduct “might” create the risk of confusion, that it was “more or less” aware of the risks, “might” benefit from the Complainant’s good will and “might” benefit from the popularity of its trademark (emphasis added).

None of this is evidence, and suspicion and equivocation are not proper tests for rejecting evidence when there is no evidence to the contrary. It amounts to an inappropriate rejection of what was a plausible case on the evidence. On properly assessing the evidence provided by the Respondent, it should have been accepted.

Nor should it be held against the Respondent, as the majority has, that it used the “.app” generic Top-Level Domain for its domain name or that the Trademark Clearing House was involved, as “.app” is one of the new generic Top-Level Domains. It must come as a surprise to ICANN, after all its time and effort spent on promoting the new gTLDs, to find that registering a domain name in the “.app” space is now held out as a reason for setting the domain name aside. Moreover, the obligation in using the Trademark Clearing House is “not (to) infringe on the trademark rights …”, which the Respondent has not done, and it was never the intention that a domain name would be negated simply because a registrant had availed itself of the procedure.

Indeed, as the Respondent rightly submits:

“It should also be noted that .APP is a ‘new gTLD’ with a Sunrise Registration period, and subject to the protections of the Trademark Clearing House (TMCH). (A copy of the TMCH Notice for the Disputed Domain is attached as 2nd Supp. Reply Exhibit 1). Complainant’s trademark was listed in the TMCH, and had Complainant really believed that the Disputed Domain was inextricably linked and central to its product and trademark it could have registered the Disputed Domain during Sunrise and before the general public. See ‘https://newgtlds.icann.org/en/about/trademarkclearinghouse’.” (emphasis added).

The Complainant therefore seems to have both ignored its own scope to register the domain name and waived its objection to the Respondent registering the domain name. No reason has been advanced why the Panel should not act on that waiver.

There is also an air of unreality about the Complainant’s case as a whole to which the majority should have had regard. The Complainant in effect contends, first, that it has the right, without any evidence of ownership or agreement from the owner or anyone else, simply to take the name of this famous object and use it as its trademark, but secondly that the Respondent has no right to register the same name as a domain name for a purpose well outside the scope of the trademark and within the normally accepted meaning of the words themselves. That is a very dangerous argument and seems to have no legal or logical basis.

This panelist’s opinion on the issues will now be examined in some more detail, to show, first, that the Complainant has a trademark on which it can rely and that the disputed domain name is identical to that trademark. However, it is also this panelist’s opinion that, on the evidence, the Respondent has a right and a legitimate interest in the domain name and did not register and use it in bad faith.

Identical of Confusingly SimilarThe majority of the Panel has held that the Complainant has established a trademark and that the disputed domain name is identical to that trademark. That is correct, as the Complainant has put in evidence seven registered trademarks for ROSETTA STONE, four with the USPTO, two with the EU and one with the Canadian authority (“the trademark”). The trademark enables a finding under the first of the three elements in the Policy that the Complainant has established rights in a trademark, giving it standing to bring this proceeding.

However, the trademark does not give the Complainant the exclusive right to use the words Rosetta Stone, or prevent anyone else from using the same words in a domain name. The Complainant undoubtedly has the right to use the words and mark ROSETTA STONE for computer software used with teaching and learning foreign languages. But it also claims that its trademark is not limited to the goods and services described in its trademarks, but that it extends far beyond those terms to the point where it is unlimited and that the Complainant has the exclusive right to use the expression for any purpose. It submits that its trademark gives it:

“the right to prevent any use of the well-known trademark or a confusingly similar denomination in connection with any products or services (i.e., regardless of the list of the products and services for which the trademark is registered). Thus, the protection for ROSETTA STONE goes far beyond language learning program.” (emphasis added)1 .

The basis for making such a claim is said by the Complainant to be Article 6bis of the Paris Convention and Article 16.2 and Article 16.3 of the TRIPS Agreement. But that is not so. Neither document justifies the statement that the Complainant’s trademark rights actually prevent “any” use of the mark with “any” products “regardless of the list of the products and services for which the trademark is registered”.

Accordingly, the Complainant’s trademark gives it the right to use ROSETTA STONE within the terms of the trademark itself. But it does not prevent other uses of the same expression and in particular it does not prevent the Respondent or anyone else from showing that it has a right or legitimate interest in the disputed domain name. It also does not prevent the Respondent from showing that it did not register or use the domain name in bad faith.

Rights and Legitimate InterestsThis panelist concludes that the Respondent has shown a right or legitimate interest in the disputed domain name and that the Panel should so find. As has just been observed, the Complainant has a right to prevent the Respondent and other parties from using the words Rosetta Stone in relation to computer software for learning and teaching foreign languages, as it has trademarks to that effect. But the Respondent and other parties also have the right to use Rosetta Stone as a domain name provided they comply with the domain name law and the principles generally accepted as being part of it.

The Respondent derives its right to use the words as a domain name from the fact that they are a well‑known, common use of language and are so much part of the ordinary language of the community that the Respondent has as much right as anyone else to use them in a domain name, provided it does not engage in targeting of the Complainant and its trademark or engage in other inappropriate action. In any event, the majority of the Panel has found that there is no direct evidence of targeting in this case.

The Respondent’s right to the domain name comes about in the following way. First, the words of the domain name invoke the physical object called the Rosetta Stone. That is the position of the Complainant itself and it concedes that its translating software “was then named ‘Rosetta Stone’ after the artefact that had unlocked the secret of Egyptian hieroglyphics for linguists”. As is well known, the famous object was “discovered” at Rosetta in Egypt and taken by Napoleon from the Egyptians, liberated by the British at the end of the Napoleonic wars and conveyed to the British Museum where it remains. Neither country has returned the stone to Egypt.

Secondly, the words “Rosetta Stone” have taken on a popular meaning that has worked its way into and has become part of the language. The words have come to mean the key to unlocking any area of knowledge or information which leads to something that was hidden. The Respondent has proved this by evidence of a series of examples from Wikipedia that are in modern parlance, where the expression clearly means using knowledge to lead on to other discoveries. The words “Rosetta Stone” are therefore part of the common discourse of mankind and should be treated for domain name purposes in the same way as other common, generic or dictionary words and as the property of anyone to use, provided its use does not come in conflict with any other principle like the ban on targeting.

Even during the currency of this proceeding, the Respondent’s counsel was able to point to a dramatic, modern use of the expression in the context of current affairs, where one piece of knowledge leads to another:

“CNN posted an article regarding Robert Muller’s investigation characterizing the Michael Flynn sentencing memorandum as ‘Muller’s Rosetta Stone’. Callan, Paul, Flynn Memo Reveals Part One of Muller’s Rosetta Stone (2018) last visited December 7, 2018, ‘https://www.cnn.com/2018/12/05/opinions/flynn-sentencing-recommendcallan/index.html’. See also (Screen Shot of the CNN Article attached hereto as Supp. Exhibit 2).” (emphasis added).

The Respondent therefore has a right to register a domain name consisting, as it does, of the name of the famous historical object and, as part of the common language, meaning the key to unlocking knowledge which leads to another area of knowledge.

The question then remains whether this explanation by the Respondent is supported by the evidence. The Respondent has given evidence to the effect that its intention – which it has started to manifest – is to use the domain name “to reflect its own brand for a product that helps uncover the unknown of the ocean and allow scuba divers to safely and properly locate, monitor, and schedule dives”. The evidence is that it is developing an app for that purpose.

It is clear that the work the Respondent has done so far is not seen by the majority of the Panel as adequate. This panelist takes a different view. The role of a court or tribunal in such circumstances where the matter might be in doubt is to see if there are any indicia that might tend to tilt the scales in one way or another. In the present case, there are certainly factors that tend to suggest that the Respondent’s explanation may well be correct; one obviously cannot be certain about it, but it is plausible, which is the real test.

Those factors in the Respondent’s favour are: that its explanation is not a recent invention as it has been working on this project for several years; the Respondent has been a professional scuba diver and it’s therefore understandable that it would be working on a project to further that work by modern means of communication; its proposal fits easily within the common meaning of Rosetta Stone; the project seems a normal extension of its previous activities; a dive site in the Philippines of which it is aware is said to be known as “Rosetta Stone”; the forerunner of the Respondent’s project is in use and has 7,000 stores listed in the app; there has been no passing itself off as the Complainant, no targeting, no misleading of the community and no indicia suggesting that the Respondent may have had inappropriate intentions with regards to the use of its domain name. But in particular, not only has it done nothing to suggest that it is using the words to trade on them for their value as the Complainant’s trademark, but the Respondent is not even using them publicly for a purpose that comes within the scope of the Complainant’s trademark at all. There is in fact nothing that has been shown to suggest that the Respondent’s intentions have been other than it has stated them to be.

More importantly, the Respondent’s actual and intended use of the domain name comes easily within the now generally accepted meaning of the expression and other third-party uses of the expression and does not transgress any of the activities of the Complainant.

The majority’s concern seems to be that they question the Respondent’s motives, that it “might” have had inappropriate intentions, that the Respondent has taken too long to build its website and that it has had enough time to produce something more substantial to show that it really is preparing to use the domain name for underwater exploration. None of those grounds are a justification for rejecting the Respondent’s statement of its intentions. In particular, the domain name was registered in May 2018, the Respondent seems to have been building on its experience since then and prior to it, and the time elapsed is if anything less than is frequently seen in other cases involving the building of websites.

The Respondent also had to comply with paragraph 2 of the UDRP, which requires the Respondent not to use the domain name in any way that transgresses the rights of another party. It has not transgressed that paragraph of the UDRP as it has not used the trademark for computer software for the teaching and learning of foreign languages and has disavowed any intention of doing so.

Accordingly, this panelist concludes that the Respondent has a right to register the domain name, that that right is supported by the evidence and that it has not been negated.

UDRP decisions are not precedents, but it is interesting that a three-person panel unanimously decided a similar case in the way foreshadowed above in dealing with another historic object. In Parnassus Investments v. ZULFIQAR ALI,NAF Claim No. 17392342, the domain name was <parnassusgroupllc.com> and the trademark was PARNASSUS, after Mount Parnassus, the home of the Delphic Oracle. The panel held that “parnassus” was being used as a generic word and could form the basis of a domain name that the Respondent has a right to register, provided that it had not “targeted Complainant, passed itself off as Complainant, pretended that it is in the same field as Complainant, or engaged in any other untoward behaviour that deserves censure and which might deny Respondent’s right to register and use the domain name”. None of those features were present, as they are not present in this proceeding.

It should also be said that the majority decision is, with respect, inconsistent with the trend of decisions on generic and common language domain names, collected in a recent article.3 Of particular value is the reference by the learned author to those words that are protected as generic because they are “circulating in world cultures”. One could ask what expression could be more part of world culture than one of its most seminal sources, Rosetta Stone?

Having regard to all of those matters, this panelist finds that the Respondent has shown a right or legitimate interest in the disputed domain name.

Bad FaithNothing has been shown to suggest that the Respondent has been motivated by bad faith in registering or using the domain name. The comments made under the previous heading are sufficient to show the same result here under Bad Faith. As the Respondent had a right to register the domain name, it could not have been registered in bad faith. Nor have any other of the indicia of bad faith been shown, other than by conjecture. There was no discernible bad faith in the registration or use of the domain name. Moreover, there is nothing to raise any suspicion that the Respondent registered or used the domain name to act adversely towards the Complainant or with the Complainant or its trademark in mind. In that regard, the principle discerned from Telstra v. Nuclear Marshmallows, WIPO Case No. D2000-0003 is clearly not applicable in the present case, as the evidence is unequivocal that the Respondent intended to make an active and entirely legitimate use of the domain name, in clear contrast with the situation in the Telstra case, where that was not the intention of the registrant.

This panelist therefore finds that the Respondent did not register or use the domain name in bad faith.

The Hon. N A Brown QC

Panelist (Dissenting)

February 27, 20191 Complainant’s First Supplementary Filing.

2 The present panelist was Chair of the panel in that proceeding.

3 http://www.circleid.com/posts/20190224_dictionary_words_functioning_as_trademarks_are_no_less/.